This blog post is late, just like a lot of the others and a lot of stuff in my life (filing my tax return, losing my virginity, etc etc.)

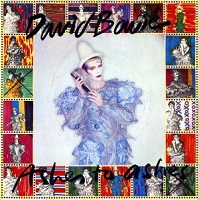

On Monday morning, I read the obituary of J.G. Ballard in the newspaper. Monday evening was the series premiere of Ashes to Ashes, the Eighties time-travel police drama.

On Monday morning, I read the obituary of J.G. Ballard in the newspaper. Monday evening was the series premiere of Ashes to Ashes, the Eighties time-travel police drama.

Ashes to Ashes is set in 1982, a time of my life when the black dog of depression had already moved in on me, and I was darkly cynical. I listened to Elvis Costello albums and read Dostoevsky and Oscar Wilde, and I knew the price of everything and the value of nothing.

Ashes to ashes, punk to funky

We know Major Tom's a junkie

Strung out in heavens high

Hitting an all-time low

Punk had been and gone, and the charts were filling up with dross again. 2-Tone let different races mingle, and dance together, but it didn’t stop there being two million unemployed. The New Romantic movement meant that people like Jonathan Ross were allowed to become famous. Bowie was still good for a couple more years, but Roxy Music had deteriorated into some sort of soul band.

The show captured my feelings well. Apart from the Gene Genie and Bolly-Knickers, who are the hero and heroine and therefore have to look good at all times, everyone around them was drifting into an abject state. Not tough, not soft, not principled, not a-moral; just strung out and getting low. The sex was nasty and loveless, the prostitutes were unhappy and not nice to look at, and even the arrival of Princess Margaret and a giant pink penis failed to improve the mood.

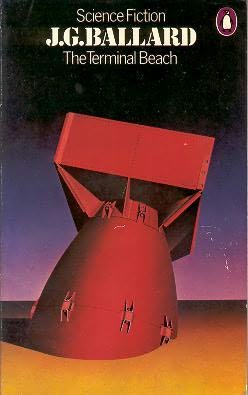

JG Ballard was a science fiction writer who wrote about the twentieth century, and the imagined twenty-first, as though he were dissecting a corpse trying to establish how it died. He describes a civilization that’s lost, only we are inside it, and losing ourselves with it right now. I discovered his work when I was sixteen, round about the time my father died, thanks to a friend I used to borrow records from, who lent me this paperback.

JG Ballard was a science fiction writer who wrote about the twentieth century, and the imagined twenty-first, as though he were dissecting a corpse trying to establish how it died. He describes a civilization that’s lost, only we are inside it, and losing ourselves with it right now. I discovered his work when I was sixteen, round about the time my father died, thanks to a friend I used to borrow records from, who lent me this paperback.

Ballard was trained in medicine and for part of his childhood, he and his parents were interned in a prison camp in Shanghai. I had a chronically ill father, and both my parents spoke endlessly about the war, so Ballard’s stories seemed like pointers to my own future, in a world where my father’s visions partially came true, and I was an adult capable of inhabiting this savage, whimsical, collapsing scientific experiment. I would become an illuminated man with “arms like golden cartwheels, his head like a spectral crown”.

Today (I mean Monday) I remember one scene in particular from ‘The Terminal Beach’. The earth is much hotter, and London has become a tropical rainforest, and the narrator is trying to make himself a home on an abandoned scientific testing station, while grieving the deaths of his wife and son.

One day, he finds some large charts showing mutated chromosomes, and he takes them ‘home’ and hangs them on the walls of his bunker. They are his art, but he doesn’t like the pictures not having any titles, so he begins to make up titles for them. Then, one day, “passing the aircraft dump on one of his forays, he found the half-buried juke box, and tore the list of records from the selection panel, realizing that these were the most appropriate captions.”

“Thus embroidered, the charts took on many layers of associations.”

Today (I mean Monday) I remember one scene in particular from ‘The Terminal Beach’. The earth is much hotter, and London has become a tropical rainforest, and the narrator is trying to make himself a home on an abandoned scientific testing station, while grieving the deaths of his wife and son.

One day, he finds some large charts showing mutated chromosomes, and he takes them ‘home’ and hangs them on the walls of his bunker. They are his art, but he doesn’t like the pictures not having any titles, so he begins to make up titles for them. Then, one day, “passing the aircraft dump on one of his forays, he found the half-buried juke box, and tore the list of records from the selection panel, realizing that these were the most appropriate captions.”

“Thus embroidered, the charts took on many layers of associations.”

1 comment:

I understand Dostoevsky.

I do not understand Elvis Costello.

But I do like the idea of the poster on the wall. :-)

Post a Comment